Law's toxic mistake problem

I’ve dealt with thousands of crises in my life, a few of which have actually happened

I struggle a great deal with making mistakes. There are times when I find myself worrying disproportionately about making a mistake, to the point of it being a real hindrance.

To take a recent example – I was sent an extra 1,000 pages of documents the evening before a two-day trial – absurdly late, and far too late to be able to prepare as well as I would usually want to. Then despite having only a very limited amount of time, I spent a number of hours of that time doing little more than worrying I wouldn’t be able to prep the case properly, that I’d miss a key point or in some other way mess it up as a result, and that it would be a complete disaster. The irony being, of course, that in worrying so much I did little more than reduce even further the time I had.

And for all those times when I notice that I’m worrying too much about making mistakes, there are doubtless plenty more times when I’m doing exactly the same, but not even noticing.

Perfectionism

My historic rationalisation of this trait was straightforward: label it ‘perfectionism’, pretend to be aware it’s not ideal, but secretly take pride in my perfectionism because really it means I produce work of the highest quality. It’s one of those non-answers to the classic interview question of ‘what’s your greatest weakness?’

However this is at best incomplete, and at worst harmful, as a way of thinking about making mistakes. A large part of this mindset comes as a result of my legal training – I’ve been taught to think this way, which reveals something important about the world of law that must be recognised and accounted for, to mitigate its negative side effects. Our approach to making mistakes is broken and unhealthy, and we need to open our eyes to this.

But mistakes are bad, right?

How can it be an issue to try and avoid making them?

On the one hand, yes of course, the surface-level response is that mistakes can be very negative and avoiding mistakes can be a perfectly good and simple goal. I'm not pretending that mistakes are just fine and dandy; they can obviously be a big deal.

But on the other hand, it is fundamentally impossible to improve at something without making mistakes; otherwise there would be no need to improve. And some mistakes are more important than others.

The famous (albeit oversimplified) rule is that it takes 10,000 hours of practice to achieve expertise or mastery. This is a vast amount of time that’s spent, inevitably, making mistake after mistake after mistake. Some of the best ideas and inventions across human history, including penicillin, smoke detectors and super glue, have been mistakes.

In many areas of life, mistakes are seen as both an ordinary and an important part of being human, and of improvement. Mistakes aren’t simply ‘bad’ – there’s a nuance to the subject of mistakes when it's approached thoughtfully. For example, modern education teaches children that when you lose, you learn, that mistakes are a crucial part of success and that they form a pathway to excellence.

I’ve missed more than 9,000 shots in my career. I’ve lost almost 300 games. Twenty-six times I’ve been trusted to take the game-winning shot and missed. I’ve failed over and over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed.

Michael Jordan

In law, by contrast, a mistake is almost universally seen as an entirely negative event, often a harbinger of doom. We are taught as lawyers to avoid mistakes at almost all costs, and to seize upon the mistakes of others.

This is an institutional-level mindset we hammer into people from the start of law school. Of course, sometimes it is useful to ask ourselves: What’s the worst-case scenario, and how do we protect the client and the case against that? Then, what’s the next worst, and how to protect against that? However, for an experienced lawyer, this laser focus on potential crises can become so automatic that it causes problems. It’s not always helpful to devote our attention to imagining how disastrously wrong everything might go.

Our 'perfectionism' can become a destructive mindset.

As important a point as any is that it’s exhausting to think in this way all the time. If what I've said so far resonates with you, that’s a likely indicator that you’re a conscientious person, and you’re unlikely to actually make a serious mistake even if you don’t observe all of your own actions like a hawk. Often, the hyper-vigilance we practise as lawyers is unwarranted. Indeed, we are perhaps more likely to make mistakes if we exhaust ourselves worrying about every little thing.

What we can do about our attitude towards mistakes at work

Have you ever found yourself reading a relatively simple email three times before sending it, and then re-reading it again after you’ve sent it? I know I have - meaning I’ve spent twice as long dealing with it when it wasn’t even a big deal in the first place. Wasted time, which I can’t validly charge money for, and a drain on my resources (not least of which is my finite ability to focus and concentrate).

The legal system as it’s been built can have such small margins for error, on top of which we’ve created such a vicious culture around mistakes, that mistakes carry a disproportionate psychological potency. It’s a harmful mindset that’s bad for you and bad for your clients. And whilst you may not be able to change this fact about where you work, you can change how you think about it and how you protect yourself.

What we can do, usefully, having noticed an unhealthy and disproportionate attitude towards making mistakes, is to be mindful of what things warrant what level of concern. If a document isn’t critically important, perhaps just proof-reading it once would be enough?

If you're a recovering perfectionist, like me, consider challenging yourself to finish a document when it’s very good or even – controversially – merely good enough, but before it’s perfect.

How important is this issue? What are the potential consequences? How much time and attention does this deserve?

These can be very useful questions to ask.

The most authoritative and reassuring people aren’t those who don’t worry about anything, and they aren’t those who take everything seriously. The most authoritative and reassuring people are those who have the quiet confidence to know which things need to be treated with due care and concern, and which things don’t need worrying about. People who command respect for the value of their time and attention. This quality is something we can model to our clients and in turn, (sometimes, perhaps) they will improve those skills in themselves.

Another perspective can be found by contrasting this with the instinct (which I certainly recognise in myself, since I think it’s a product of having empathy) to treat every problem, concern or issue a client brings to you with equal priority. The client has a problem, you act for the client, so your job is to take that problem seriously and show how much you care, right? Wrong; duplicating their mindset isn’t bringing anything different or valuable to the table.

If you don’t make the effort to take a step back and evaluate the importance of what they bring – and by extension how much you need to worry about it – then you’ll end up wasting time and money, and you’ll advance all the bad points along with the good, thus diluting your argument or your case into a worse one. That isn’t helpful.

Clients need you to use your skill, experience and expertise to be more discerning than they are and to differentiate between issues, calmly deciding what to prioritise.

When I first qualified I would treat every page of the papers with the same reverence, pouring over ever line on every page, whether it be the blurb in the middle of a house valuation report, the passive-aggressive email exchanges buried in the correspondence file, or the key line of someone’s witness statement. And when I was starting out this was necessary – I needed to learn the difference between the wheat and the chaff – but my approach has refined over the years.

What’s odd and a little disconcerting is that I now spend a lot less time reading the papers in a case than I used to. At first blush this seems like a scary thing to admit; people may think I don’t work as hard and so shouldn’t charge as much or be trusted as much. But actually, I don’t necessarily spend less time working on a case, rather I spend my time differently. Now I will spend much more time on one line, or even one word, of that witness statement, and much more time reflecting on the strategy of a case overall, and in so doing I return much more value to my clients.

Remember those extra 1,000 pages I received? The hardest thing about that experience was making my peace with the fact that it was impossible to read them all, and finding the bravery to trust my instincts and experience about which of them might really be important.

That allowed me to devote the majority of my remaining time to the small percentage of the new pages relevant to the strategy I had in place, with the result that the following day at court went well, and we were able to secure an outcome our client deserved, including a costs order. That makes it sound like I didn’t make a mistake at all – but I did. My mistake was wasting precious time and energy worrying unnecessarily. Thankfully it didn’t impact my client on that occasion, but it did impact my ability to get a good night's sleep.

The difference between I am a screwup and I screwed up may look small, but in fact it’s huge. Many of us will spend our entire lives trying to slog through the shame swampland to get to a place where we can give ourselves permission to both be imperfect and to believe we are enough.

Brené Brown

In the face of fear of mistakes, be brave in taking an approach premised in having faith in yourself. You’ve probably not made some massive phantom error that’s undiscovered, and if you have, then you can handle it when it comes, and that time spent over-focused on mistakes is time that could be put to better use.

And framing all the worrying as perfectionism? I think actually it’s a version of imposter syndrome, a way of mis-characterising insecurity as something non-threatening and a way to avoid doing the really hard thing, which is to work smarter, not harder. In an environment where working hard and being busy are fetishised, that’s a true challenge.

Taking this mindset home with you

Another risk associated with our trained aversion towards making mistakes at work is that it can too easily creep into the rest of our lives.

On a subconscious level I think I have a default assumption that any mistake I make is a total disaster, even when I’m not at work. My mind automatically extrapolates from any possible mistake (i.e. I worry about these things long before they might ever even happen) to the absolute worst-case scenario. And because it’s been trained into my subconscious, it can permeate into situations where that level of concern is totally disproportionate.

I fully admit to having spent half an hour choosing what film to watch on Netflix of an evening, out of fear that there’s a better choice available, to the point where I can’t start watching because it’s then too late. If I’d just chosen a decent film in the first few minutes, I’d have forgotten all about the possibility of a ‘better’ option within 30 seconds of the opening credits. But instead, I missed out altogether.

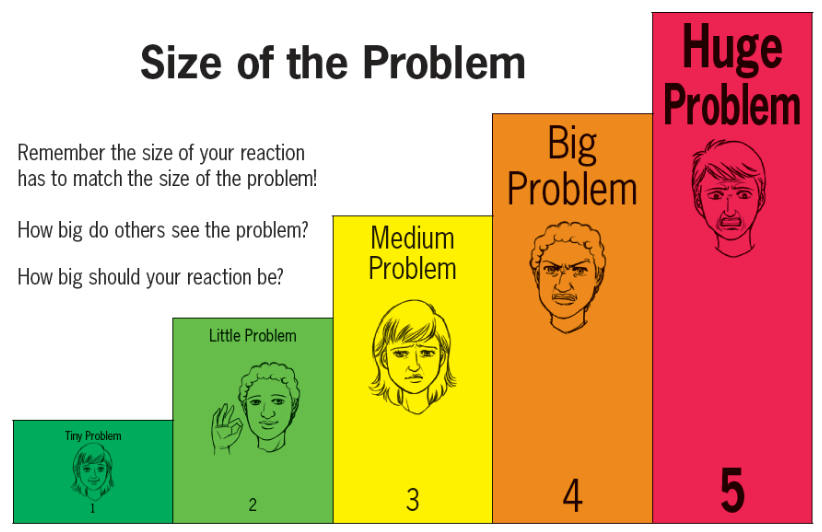

A common teaching tool for primary school children to learn about emotional regulation

Most decisions aren’t life-defining and don’t need to be poured over to the Nth degree of detail. Often in life, there just isn’t a single best option or a single right answer to be discovered. There are lots of different choices, many of which may work just fine and where, perhaps, simply trusting your gut instinct or being led by an emotion as to which to choose is a far simpler and less stressful approach.

But my lawyer mindset doesn’t easily appreciate this, rather it makes normal day-to-day decisions unnecessarily high-stakes and overly complicated, often to my detriment.

Conclusion

The psychological weight of the perceived consequences of making mistakes is such a massive burden. But not all mistakes and not all risks are created equal; we need to be more discerning about how and where we spend mental energy. This way, we make a more manageable and realistic working life for ourselves and provide a better service to our clients.

A related article about mistakes at work by Brené Brown can be read here.

Today’s video is a joyous performance of Christopher Tin's Waloyo Yemeni, sung by Jimmer Bolden and Allie McNay.

Today's recommended track is Don't Look Back In Anger by Oasis.

If you like my content and would like to support my work, I'd be very grateful if you would consider subscribing with the link at the bottom of the page.

--

Get in touch if you’re interested in any of my services. As well as a barrister I’m also a trained mediator, hybrid mediator and high conflict specialist.

My legal services are offered separately via my chambers website; my clerks manage my legal and mediation work and their contact details are here. I also offer in-house training on a variety of subjects including first client meetings. I offer individual and firm-wide consultancy on improving productivity, wellbeing and communication. To get in touch with me direct, please subscribe then go to the Contact page above.